BOOK ANNOUNCEMENT

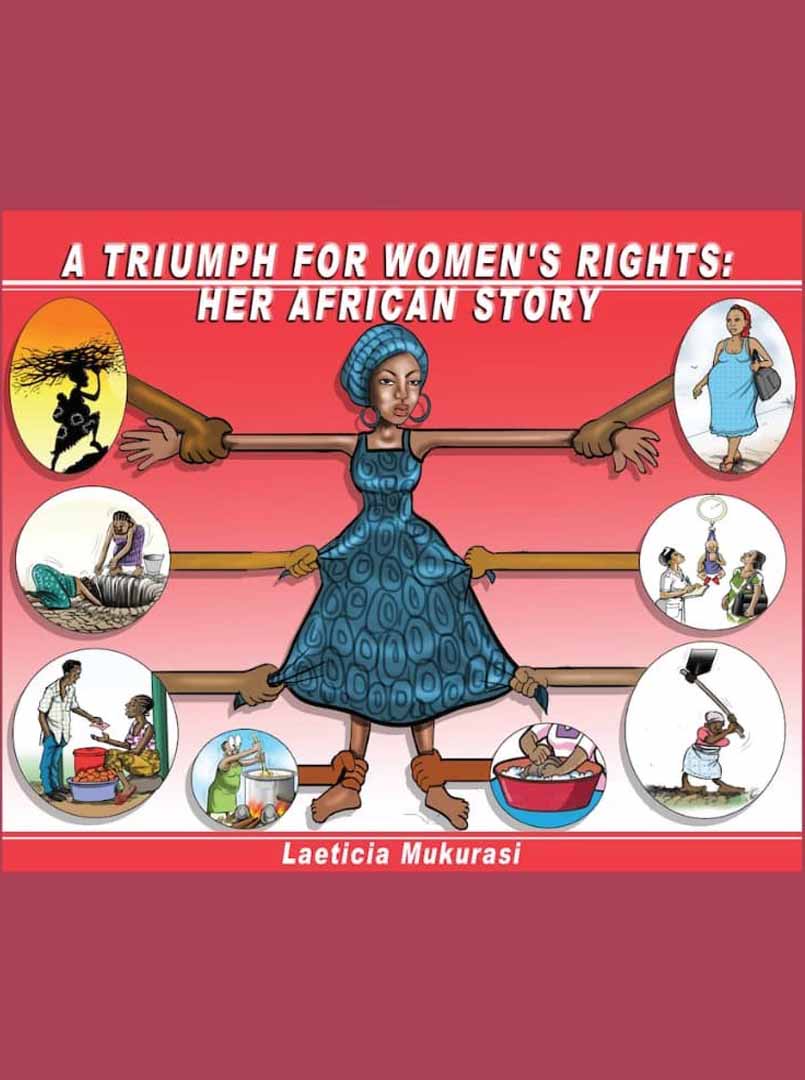

A TRIUMPH FOR WOMEN’S RIGHTS: HER AFRICAN STORY

The whole world is engaged in a 25-year review of the implementation of the Beijing Declaration which was hailed as landmark commitment for achieving gender equality. To commemorate this silver jubilee, I have written a book that seeks to contribute to the on-going discussions and stock-taking exercises of its execution. The book documents my experience of working as a Chief Gender Specialist at the African Development Bank in the years 1998-2010”.

A single-sentence summary of the book that captures its core argument and appeal

African woman employee fighting a huge, powerful global institution on behalf of women’s empowerment meets a patriarchal institutional status quo and wins through against summary dismissal for challenging her boss’s sexist statements.

- TZS 20,000/= (plus 10,000/= for postage outside Dar es salaam,

you can pay via M-Pesa number 0764682634 ) - USD 18

- GBP 12

- EURO 15

-

Book Chapter Summaries

PART 1: THE STRUGGLE FOR WOMEN’S RIGHTS1998Chapter 1: IntroductionThe introduction begins in flashback style and provides the conceptual framework for the book. It presents brief details of my education, work experience and the factors that inspired me to write this book. I entered the African Development Bank in 1998 feeling empowered, highly motivated and with a great sense of purpose. I describe my hope, vision and ambition for what the Bank could achieve: it had the potential to catalyse the gender equality revolution on the African continent and to make a difference in women’s lives. My main objective was to support the Bank’s work to enhance gender justice on the continent.Chapter 2: The Organizational ContextThe chapter details the contextual characteristics that inspired my work: the desire to alleviate the extreme poverty in Africa, in particular the feminization of poverty; the fit between the Bank Mandate, Mission, Vision and the gender mainstreaming strategy and its positioning as sole regional development financial institution which gave it status, authority and comparative advantage to influence the direction of development on the continent.Chapter 3: Structuring Gender Work for InequalityI discover that I am the only person whose role is to mainstream gender work in the entire Bank comprising about 450 professionals! Close to 81 percent of the professionals are men and management is 90 percent male. So, my success is going to depend on how I engage men as a strategic part of the process. The remaining part one chapters concern my strategies to promote gender mainstreaming in the BankChapter 4: Forging RelationshipsI find out that I am reporting to an environmentalist with limited knowledge of gender. This chapter discusses my strategy to work with my manager to ensure effective representation and articulation of women’s views at the decision-making table.Chapter 5: Taking ChargeI work to establish the status of gender work and to determine the way forward. An important finding is that the quality of gender analysis in project design is inadequate to achieve mainstreaming of gender equality in the Bank’s lending programme. This is of grave concern given that the programmes/projects are the main mechanism through which financial resources has the potential to address gender inequality, empower women and reduce poverty. I develop a work plan. At the same time, I begin to face unwelcome comments, slurs and “jokes” on gender. These convey an informal message that gender equality is not taken seriously. I feel disrespected but decide not to tackle the issue head on, fearing its escalation.1999Chapter 6: The Portrayal of Gender/Women in Bank ProjectsThis is a key chapter and an important pillar in this work. Attention is centered on the unsatisfactory quality of gender analysis in the design of Bank projects and on why Bank projects fail to adequately promote gender equality. My analysis reveals a failure to adequately portray women’s strength and potential for Africa’s development and their centrality in enabling households to escape poverty, sustaining livelihoods and promoting economic growth. This lapse in the analysis reflects, in part, the influence of the neo-classical economic paradigm which treats women’s work as unpaid and therefore “un-economic”. There is often no analysis of power relations, the disparity in access, ownership and control of resources. Little attention is paid to the multiplicity of tasks and the conditions under which women do their work including time poverty, lack of adequate infrastructure (e.g. water, energy, roads) and use of primitive or rudimentary technology. Such practices are buttressed by the reliance on labour statistics whose conceptual underpinnings also emanate from the neoclassical economic school of thought and are largely gender-blind. Such practices have the potential to lead to the adoption of inappropriate policy responses and outcomes. I outline my checklist for deepening the level of gender analysis.Chapter 7: Strategies for Establishing Institutional Presence, Voice and VisibilityI take steps to deal with the marginal positioning of gender in the organizational structure. I identify areas where I could take control and influence change. I use my expert power to promote my work through “e-activism”. I provide gender guidelines on how to conduct gender analysis in projects. I engage with male professionals on how to advocate for gender in meetings with regional member countries. I speak out during a town hall meeting to canvass for additional Gender Experts. I am threatened with non-renewal of my contract. I refuse to be intimidated and resolve to use every opportunity to advocate why gender equality has to be seriously treated in the Bank’s lending programme.2000Chapter 8: The Politics of Gender Policy DevelopmentThe chapter examines the process of gender policy development, its substance and the probability of its successful execution. The Bank makes several important commitments: to strengthen gender analysis in all Bank programmes and projects; to mainstream gender into the regular project costs thus obviating the need for separate budgets for women and support research that would enable the Bank to position itself on a number of critical gender issues pertinent to the continent. Accountability and responsibility for gender mainstreaming are vested in senior management. However, I worry about its effective implementation given that the implications of the policy for the Bank’s lending activities are not adequately threshed out - more than half of professional staff and members of senior management are not acquainted with the policy. My suggestions to include gender-based violence as a factor in de-stabilizing women’s access to resources and the establishment of an External Advisory Committee on gender issues as a mechanism for a women’s voice in the affairs of the Bank are rejected. Likewise, my efforts fail to move the Bank to consider a paradigm shift that would challenge the neoliberal economic orthodoxy from an African perspective and bring in “gender” as a tool of analysis are vetoed.Chapter 9: Mechanisms and Tools: Mainstreaming Gender in The Environment and Social Assessment ProceduresThe chapter discusses the efforts of a multi-disciplinary task team to embed gender and other social issues into a single major tool – the Environment and Social Assessment Procedures (ESAP). The goal of ESAP is to analyze the potential environmental and social effects of Bank activities before they are implemented. The adoption of ESAP has potential to promote the design of projects that address the political, economic and social factors that shape women’s lives differently from men. However, some colleagues are convinced that projects could not have any adverse or differential gender impact. They caution that Bank projects should not tamper with the traditions, norms and values that govern gender relations in communities. To do so would lead to the collapse of African culture. Thus, implicitly in the context of the Bank’s work, there would be no redefinition of responsibilities, rights and relations between men and women. I point out that the Bank could not promote development by maintaining the status quo. I find that this is the kind of thinking held by many in the Bank including management. I am cautioned against promoting “feminist” ideas in the Bank.2001Chapter 10: Reality Check 1: Gender Ignored in Budget AllocationsBy this time, I have been in the Bank for three years. Contrary to the requirements of the Bank Policy, initiatives to promote gender mainstreaming are not consistently or sufficiently mainstreamed in the allocation of the administrative or project budgets. I closely follow up budget allocations for capacity building for gender mainstreaming. This is the area where the drama over the administrative budget is prominently played out.2002Chapter 11: Reality Check 2: Experience of Moral HarassmentMy review of the project documents consistently reveals an inadequate level of gender analysis in Bank programmes and projects. Many of my recommendations to improve its quality are largely ignored. Expressions of dissatisfaction by the Board of Directors over the quality of gender mainstreaming become more frequent. A senior Director tells me that he holds me responsible for this shortcoming, yet I have no power to stop inadequate projects from moving forward.Chapter 12: Reality Check 3: Experience on Bank MissionsIt is four years since I joined the Bank. Feeling that my knowledge of on-the-ground issues is becoming rusty, I request to participate in some Bank missions. In this chapter, I provide vignettes that demonstrate different levels of understanding of the “gender” concept. For example, a Bank’s water engineer tells me not to turn his project into a woman’s project when I suggest the training of girls as technicians in order to ensure consistent water supplies.2003Chapter 13: The Politics of Gender TrainingSince engagement with male professionals is a strategic part of the gender mainstreaming process, I recruit a consultant to prepare a report on training needs analysis. The report reveals that most staff: i) are unfamiliar with the “gender” concept; ii) are unaware of the link between gender and development; iii) have limited knowledge of gender analysis tools. Some staff members perceive that gender mainstreaming is of no relevance for sectors such as road construction, power, and private sector enterprises which they view as gender-neutral. I facilitate training with four objectives: to increase gender awareness and sensitivity; to enhance analytical skills; to impart techniques in how to mainstream gender throughout the project cycle; and iv) to begin a process of transformation in staff mindset. However, the training programme is not comprehensively implemented due to lukewarm support from some members of senior management. Most are not trained and constitute a bottleneck to the change process.2005Chapter 14: Reflections on my Work EnvironmentIt is 2005 and I have clocked seven years’ service in the Bank. This chapter presents my reflections on my work environment, especially the lack of room for manoeuvre it provides to make a meaningful contribution to the Bank’s work. Although the Bank’s mission is inspiring, the indifference to gender work has begun to chip at my enthusiasm. The quality of gender analysis in most Bank projects leaves a lot to be desired. I begin to doubt if there is enough commitment that will lead to significant change in how the gender equality issues are treated in the Bank’s work. I spend a lot of time soliciting funds from bilateral donors for gender equality work which should be financed by the Bank. I fight hard not to be demoralized.Chapter 15: Light at the end of the Tunnel?In this chapter, I reflect with hope on three important developments which possess the potential to galvanize the Bank on gender mainstreaming. The first is the decade review of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, whose report show that there has not been substantial change for many African women, who are the majority of the poor. The second is the adoption of the Paris Declaration demanding proactive measures to track how increased aid will affect women. The third is the arrival of a new Bank President from a country where women hold 49 percent of seats in parliament. I am impressed when during his first town hall meeting, he professes to be an open-door President and welcomes staff to see him personally to canvass his support for worthwhile initiatives. I see in him a potential ally for gender in the Bank.Chapter 16: The Development of the Gender Resources and Results Tracking SystemIn this chapter I recount my effort to establish the Gender Resources and Results Tracking System (GRARTS) whose purpose is to assist the Bank to factor gender equality considerations into the criteria that determine the planning of Bank investments. This tool would enhance the potential for gender equality because it would trigger several processes that forms part of the budget allocation process. It would make it possible for Bank programmes and projects not only to track the resources allocated to increase gender equality but also to monitor changes in the gender dimensions of inequality that result from Bank investments over time. This was meant to be an important milestone and a flagship activity that would distinguish the Bank as a leader and a champion of efforts to empower women on the continent2006Chapter 17: The Mid-Term Review FindingsThis chapter discusses the Report of Mid-term Review of the implementation of the Gender Policy and Plan of Action, which focuses on whether the design of Bank projects has the potential to promote the achievement of gender equality. The report commended the Bank for the steps taken and noted an enhanced level of gender analysis and the integration of gender related interventions into some projects, including indicators into the results framework. However, only 33 per cent of the projects assessed demonstrated gender analysis best practice. The review showed that most documents do not contain baseline gender disaggregated data to establish the accurate situation of women and men. Moreover, many projects do not problematize unequal gender power relations, time poverty and women’s heavy work-loads as potential barriers to gender equality. Armed with the Reports on the Mid-Term Review and the Gender Resource and Result Tracking System, I request to meet the President for a comprehensive briefing on the status of gender mainstreaming. I do not get any response.Chapter 18: Ethical Dilemma and a Conflict of LoyaltyI recount how I was summoned to the Board of Directors meeting without warning, to account for the unsatisfactory level of gender analysis in many Bank’s documents. I am required to answer this question, before the President who is both Chief Executive Officer and chairperson of the Board. I am faced with a moral dilemma. Who should I defend, the management inside the room or the women’s constituency out there? Dare I admit management’s indifference and lack of accountability for gender work? it is a classic case of role conflict. I reflect on the efficacy of the Bank’s governance structure, particularly its lack of a system of checks and balances to regulate the respective powers of the President and the Board. Who bears ultimate answerability for gender mainstreaming? I manage to deflect the question but leave the room feeling like a fraud.Chapter 19: Missed Opportunities - Gender Included as an after thoughtThis chapter discusses how as Chief Gender Officer, I am excluded from activities that would give gender mainstreaming greater traction. I am usually called to meetings last, with little preparation to meaningfully participate and contribute.Chapter 20: More Missed Opportunities: The Berlin Conference on Women and Economic EmpowermentThis chapter is about my shattered expectations when a senior officer of the Bank goes to an important donor meeting focusing on women in Africa and comes back empty handed.Chapter 21: Silver liningsIn this chapter, I recount my appreciation when the Bank’s Gender Policy receives a top ranking in an international publication on gender justice in international financial institutions. Excited, I send out an email message announcing the good news. The only response from senior management comes from the Vice President of Infrastructure who calls on my expertise and consequently issues a directive urging his staff to begin the process of identifying specific actions to ensure that the goals and objectives of the Gender Policy are effectively mainstreamed in project design. Further, he directs all the directors working in his complex to release staff for gender training and to put in place an action plan on how to operationalize gender mainstreaming in infrastructure projects. I am thrilled.Chapter 22: Lost in the CorridorsWell into my tenth year, I am forced to confront and ask myself some hard questions: will it ever be possible to trigger a deep enough change in the way gender issues are treated in the Bank. My key efforts to get the Bank to deepen the level of gender mainstreaming are again thwarted and blocked before they get to senior management. I begin to feel exhausted and fall ill. My doctor advises me to consider a move from gender work.2008Chapter 23: Mission ImprobableI must seriously consider my doctor’s advice to transfer from my gender specialist role but decide first to request a meeting with the President. My attempt receives no response. I make a last-ditch attempt to bring attention to the limited progress in gender mainstreaming, through a note to the human resource manager, expressing at length my concerns and evidencing how my efforts to embed gender mainstreaming are being ignored and blocked. I request him to circulate the note to members of senior management. On learning of my note, my Director threatens to fire me for divulging his department’s “secrets”.Chapter 24: AmbushedI narrate how, a month later, without prior notice, I am summoned by the President to a meeting of senior management. The President asks me what was going on with gender in the Bank. I need to choose my words carefully. I recall my note to the human resource manager, try to avoid finger pointing and summarize five key messages. Given that my requests to meet him had been rebuffed, I wonder why the President found it necessary summon me to answer questions in front of both my manager and Vice President.Chapter 25: The Last Straw: Women Bureaucrats - Allies or FoesI am task manager for the Gender Plan of Action Update. A day before it is tabled before senior management, I get an email message cancelling the meeting. At the same time, I learn that I have been transferred from one vice-presidency to another. The cavalier manner in which my work is publicly stopped, without warning or negotiation, is hurtful. Six months later I take action to transfer away from gender work. With hindsight, I conclude that I was transferred to the new vice-presidency to rein in my what was considered as my feminist outlook.PART 2: THE STRUGGLE BEGINS WITH ME2009Chapter 26: The Meeting with the PresidentI am told that my request to move from gender work is blocked by the President. I request a meeting with him to plead my case. During the meeting, the President accuses me of being a troublemaker; of being ambitious; of wanting to be promoted at any cost; of being a feminist and of pursuing a feminist agenda not a gender agenda in the Bank. I am deeply shocked. This is my first meeting with him and he does not supervise me on daily basis. Moreover, none of my immediate supervisors had ever given me a warning over my character or performance! I have the presence of mind to ask for his definition of feminism and the link between the feminist agenda and gender agenda. I get no response. I leave the meeting feeling angry and distressed. My health collapses and I am hospitalized. I am given leave to transfer from gender work.Chapter 27: I Move to the Human Resource DepartmentStill feeling shell-shocked from my encounter with the President, I begin work in the Human Resource Department as Chief Diversity Officer. Feeling a great psychological burden, I become reclusive, fearing and suspecting everyone. I analyze the meaning of the President’s verbal attack in the context of the woman question and the fight for women rights. I conclude that the President’s statements are discriminatory and sexist and do not conform to the ideals and values of the Bank. They are also totally at variance with my character and contribution to the Bank’s work. I weigh my options on whether to tackle the issue or remain silent. Pursuing it could cost me my job. Silence would mean that I condone his actions.Chapter 28: Measures Taken to Find a SolutionThis chapter contains an account of how a few months after my meeting with the President, I muster enough inner strength to address the issue. I am aware of the power dynamic – questioning his statements could result in the end of my career. Nevertheless, the matter is too serious to be let go. His words constitute a breach of trust - an implied term of a psychological contract. As an advocate for women rights, it would be amiss to let the President’s behaviour pass unchallenged. I see that the fight for women’s rights starts with me. How can I defend the rights of others if I cannot defend my own? I write to the President requesting for clarification of his statements and inform him that I find his characterization of my person and my work not only intimidating but also detrimental to my performance.2010Chapter 29: I Lodge a ComplaintWhen three months later, I had not received any response, I decide to hold the President accountable for his statements. Not wishing to escalate the issue beyond the confines of the administration, I write to the Vice President of Corporate Services requesting an inquiry. I know that questioning the actions of the President runs counter to the dominant culture of deference to an authority figure. Moreover, for a woman to confront such a powerful man will be perceived as culturally inappropriate and a contravention of the unwritten code that requires women to be respectful and submissive to men. In my letter, I am careful to adopt a factual approach, tactful yet uncompromising on issues of principle.Chapter 30: I am DismissedTwo days later I receive a letter from the Vice President of Corporate Services that my employment with the Bank is terminated with immediate effect and without notice. It alleges that my description of what was said at the meeting was not only false but that it was clearly aimed at “tarnishing the image of the President, undermining his authority and ultimately tarnishing the image of the Bank”.Chapter 31: No Choice but to SueObviously, the President has ordered my dismissal and has misused his power, violating the principle of due process. I see his action as a ploy to intimidate and break my spirit, to make me leave silently. On the contrary, I take steps to mount a legal challenge to my dismissal, based on the procedural and substantive irregularities in my treatment.Chapter 32: The HearingIt is a case of David and Goliath. The President is defended by a team composed of the Bank’s General Counsel with a bevy of eight Bank lawyers and one international legal consultant, all paid by the Bank. I pay for the services of my Legal Counsel. The atmosphere is electric. This is a test case for the Tribunal, given that no previous case had involved a decision in which the President was so centrally involved.2011Chapter 33: The Judgement: From a Walk of Shame to a Walk of GraceThis chapter details the Tribunal’s findings. The decision to terminate my employment is quashed. I am awarded compensation for wrongful dismissal. Goliath is vanquished. I walk proudly out of the Bank, my head high.2017Chapter 34: Conclusion: #MeTooIn this final chapter I sum up my thoughts about gender mainstreaming and how it is implemented. It was written at the height of discussions of the gender pay inequality at the British Broadcasting Corporation and the revelations of sexual harassment in Hollywood. Although my experience is not a direct fit for the #MeToo definition, which mainly focuses on workplace sexual harassment, it is nevertheless a useful as a concept which promotes a cultural transformation that encourages the powerless to question the illegal actions of the powerful. I make several recommendation on issues raised by my story including: the relevance of gender mainstreaming strategy as a coherent articulation of the women’s equality agenda; the need to accelerate the pace of progress in achieving gender equality; the imperative to bring men on board as part of the agenda-setting approach; the obligation to ensure that development projects are designed in ways that ensure that women’s time, energy and creativity are not simply used to serve development ends but also to ensure that women profit from their work; and the need to ensure women’s voices influence the Bank’s work. Last but not least, I propose the changes required in the Bank’s governance structure to ensure accountability to women and gender equality results.

Book reviews

-

Review by Dr. Hellen Bisimba

“The author has come out as a voice on issues over which there is silence in many places. Reading this narration will make all those who are evaluating the 25 years of the Beijing Platform for Action sink and think deeper, not by searching the documents in organizations but by looking beyond, in a qualitative manner how such documents are being lived and implemented” Read More...Dr. Hellen Kijo Bisimba

Human Rights Activist -

Review by Wendy Hollway

“We may know that women’s development seems to have stalled, across rural Africa and beyond and also in the global organizations that are formally committed to rectifying this situation. Here we find out how this happens. This book provides an enlightening study of an attempted organizational change and the powerful resistance to it”.Wendy Hollway

Emeritus Professor of Psychology

-

Review by Eddah Sanga

Reading A Triumph For Women's Right Her African Story facilitates a deep understanding of why documenting our stories is more important today than it was in the past.The writer, who is known as a prolific writer on gender issues has authored and co-authored several books and articles in which she criticizes how men use their power against women.In this book, the author, Laeticia Mukurasi narrates how she struggled to bring about an understanding to her bosses at the African Development Bank with whom she worked for twelve good years, that her work was meant to "promote gender equality and women empowerment issues in the bank"Unfortunately, this notion did not augur well with her bosses who saw her as a feminist pursuing a feminist agenda and not s gender agenda in the bank.The twelve-year journey was, therefore, a living testimony to the struggles long and bitter many women are forced to go through in many organizations. Reading on, it is evident women have still a long way to go before they can realize equity in rights, access for resources and power, and of course for dignity and respect.

The book brings to the fore how some men didn't have an understanding about women's year in 1975, decade doe women in 1985 and Beijing Platform for action in 1995, women were ridiculed and given a blanket name of "Beijing".

The author puts succulently how, knowing she was working with a very crucial financial institution that would make a difference to the majority of women in Africa, it was important to fight tooth and nail to raise her voice as a gender specialist in fulfillment of African women's expectations, needs and aspirations.I recommend reading the book to discover the author's unique experience in the women's struggle. It inspires, resonates strength, agility and confidence. Her lone voice may be a voice in the wilderness, but if we combine our voices with hers we shall be instituting what Malcom Gladwell said, "The tipping Point". And this will definitely make a difference.Eddah SangaJournalist, Human and Women Rights Activist. -

Review by Anabahati Mlay

As the Author narrates her own experiences as the Gender Specialist of one of the most powerful institutions, The Africa Development Bank, she also carries the readers through a history of the development of women rights in Africa from the time of the Beijing declaration.

One cannot ignore the competencies and passion that the author had for gender mainstreaming which makes the book an authority in the gender mainstreaming arena.

For a young feminist with a profound interest in gender mainstreaming this book is a manual to understanding why despite all the declarations and agreements meant to bring about gender equality, despite nations being signatories to instruments that are meant to bring about gender equality and institutions having gender policies and other instruments, gender equality has not been realized even in leading organizations.

The author has explored the root causes of gender inequalities, pointing out the lack of true intentions and both political and will power by individuals, leaders and institutions to bring about gender equality but rather paint a picture that shows adherence only to be seen as part of the efforts and sometimes as a way of attracting funding.

In this book you will feel the author frustration, and at times anger, which most gender specialists experience as they try to implement their mandate in male dominated work places. She has voiced her concerns on the issues of misinformation or zero information among people on gender equality and gender mainstreaming which makes the job of Gender Specialist a daily struggle of power with leaders and even colleagues as their job is seen by many as that of a trouble maker whose only intentions are to disturb the status quo which needs to be disturbed anyway.

It is a clear indication that despite all the strides made in gender equality from the Beijing gender agenda there is still a lot to be done to achieve true gender equality both in the society and in our institutions. This has been the biggest challenge faced by gender specialists in most organizations and it’s not news that most of female feminists are always titled as angry women or angry activists hence their job is not given the right weight in terms of resources and not treated as a core part of most organizations.

The book has also showcased how failure to implement gender equality at big institutions end up affecting women up to the grassroots. In narrating her own ordeal the author speaks for a lot of women who faces discrimination at the work place but only a few find the courage to speak up because of the pre- existing biases and unfair treatment standards that are set in many institutions despite having gender policies which in reality are only shelved instruments. She also shows how not placing gender equality at the center of our institutions rob women the right to access to different services which are already available for them.

This is not just a book about laeticia struggle as a gender specialist at the African Development Bank but rather an analysis of how far we have come in implementing the gender agenda . It is not a throw of tantrums by an angry woman but a well researched and well put account on gender mainstreaming and the problems faced by women at the workplace everyday with proposed solutions and ways to accelerate the process by starting having true intentions and political will to do the same.

It is a must read for anyone seeking a deeper understanding in the subject of gender mainstreaming.

Anabahati Mlay

Female Future Programme Coordinator- Association of Tanzania Employers. -

Review by Nicholas H. Mbwanji

Laeticia, congratulations for bringing to the surface your plight while working at the African Development Bank. Hopefully many women, and men for that matter, will draw lessons and be encouraged to fight for their rights. The book sets out the challenges you encountered while trying to accomplish your dream, that of being an "agent" for the rights of women in Africa. Having perused through your book, the battle you were fighting had several dimensions, namely:1.0 Male chauvinism – those who didn't believe that the gender equality agenda was indeed realizable – and these were those who called you names – "Mrs. Beijing is here.... So you are on mission to equalize us! Trivialization ... so you want women to be on top of us, etc etc.2.0 Male hypocrisy or two-facedness the likes of which are exposed by George Zimbizi – those who by virtue of their positions are forced to stand on platforms to hypocritically advocate for gender equality but no intention of implementing the same.3.0 Male dominance – as you point out, one gender specialist against an "almost totally male senior management team..." – being under male bosses your work was rendered almost invisible". Besides out of the 450 professionals (10 percent females; 90 percent Male) in the Bank you were the only person dedicated to gender work in the early days of your joining the Bank4.0 Management structures were not accommodative enough for the Gender agenda to be visible within the Bank's Management. Although on paper, gender and environment were supposed to be two priority cross-cutting issues! For some reason environment overshadowed gender!!!5.0 The Bank systems had not "mainstreamed the gender agenda in its structures" – there were no serious efforts to mainstream gender issues in the Bank's system – the Women In Development Unit (WID) was abolished at one point in time (and was reinstated upon your appointment).No resources were allocated to implement catalytic gender affairs, the Bank's Operational Manual provided authoritative guidance on the notorious gender paragraph!Notwithstanding all the odds as mentioned above, you personally attempted to make things happen – for evolving strategies for establishing gender institutional presence, voice and visibility. Unfortunately, some of the men whom you had expected to assist you as "gender advocates" – a male colleague who was to be part of the team to Zambia, was not comfortable to play that role, although ultimately, he was one of your allies or rather the converted!!!Your strategy was, I believe, to groom as many as possible of the converted, not only to support your move, but also to assist in bringing change or rather mind-set change about the gender agenda in the Bank. Unfortunately, it seems the converted were not that many!!Then one keeps wondering about the "gender agenda concept". It is not that much complex to understand and digest, particularly for persons with an African background, then why was there such a fierce resistance to support the concept? This raises several questions? Was it that the style used – by the promoters of the agenda (the gender specialists) - to bring about change, was causing resentment among most professionals? Did professional staff, in particular, feel that the approach used was rather "commanding/imposed" on them. Were there personality clashes? Or what was it?Having gone through your book, I am rather lost – was the "Gender agenda" imposed to the Bank? Why was the resistance emanating from the very top levels of management? Let alone male colleagues, what about the females – who seem were silent on the issue!!! Why?The President was not sure which agenda you were pursuing "feminist agenda" or a "gender agenda" – your response to this was brilliant BUT had the top management to wait for so long to realize that the Bank was not on course as far as the Gender agenda issue was concerned?Last but not least, is about good governance – effective management structures – of the Bank. As you assert in the book, the Bank President was both the CEO and the Chairman of the Board of Directors. Thus, not only did he supervise the implementation of the Bank's operations, he also chaired the sessions that assessed how the Bank's operations were executed. Specifically, and in as far as Laeticia's case is concerned, the Staff Rules – particularly the summary on summary dismissal in part reads:"Summary dismissal shall be imposed only upon determination by the President that the staff member concerned is guilty of serious misconduct..."It was the President, who was being accused, and it was the same President who was supposed to determine if the staff had committed serious misconduct– under that state of affairs, there is a conflict of interest and it would be difficult, if not impossible to exercise a fair trial. And it is possible that under those circumstances the President behaved as if he was not accountable to anyone. That amounts to abuse of power.As for the Bank's Administrative Tribunal, it is commendable that it was fair in its deliberations and ultimately its judgment. This notwithstanding, the comment that "Goliath was down" is not rational, given the circumstances under which the proceedings were conducted.Nicholas H. MbwanjiLabour Market SpecialistInterFINi Consultants Limited -

Review by Chiku Semfuko

As the author narrates her experience as a Gender Specialist at the African Development Bank, you get the feel of how gender is belittled as a woman’s issue and not as a human right. The mocking and sneers she endured as she struggled to bring the relevance of gender issues in the organisations was clear that the gender positions at the bank was just a ruse to entice European donors.

As a young gender specialist, I found that I relate on many the author’s experiences, specifically the frustration of having no budget allocation for gender activities and how gender is not given the importance or recognition it deserves. The author has certainly showcased what many gender specialist’s experience. I applaud the author’s competencies on gender and development, her resilience and determination to continue to rise against all odds.

Albeit the international instruments and declarations on gender equality, we cannot achieve the goal of reaching gender equality in the near future as the responsible flag bearers of development are not willing to hoist gender as an agenda and removing the many misconceptions on gender brought about by pre-existing biases. We need to re-evaluate our strategies, ensure that gender we bring men on board: gender advocacy doesn’t only concern women.

For anyone interested in knowing more on gender issues, I definitely recommend this book, it guides and addresses on how to tackle the challenges brought about promoting, advocating and implementing interventions on gender equality. This book serves as an intergenerational dialogue and Ms. Laeticia has certainly handed over the gender equality baton to all feminists and gender activists for many generations to come.

Chiku Semfuko

Gender Focal Point, ILO East Africa.

Laeticia's Videos about her books

#VIDEO Ms Leticia Mukurasi, a Gender and Development Specialist and Member of Gender Equality Forum in Tanzania (GEF) shares her take on the Women, Business and Law 2023 Report launched by the @WorldBank in a bid to realize Gender Equality in Tanzania. #GenerationEquality pic.twitter.com/sGB1vRyruo

— Generation Equality KIZAZI CHENYE USAWA (@GenEqualityTZ) March 27, 2023

Laeticia's Other Books

-

Post Abolished book description

“Post Abolished: One woman’s struggle for employment rights in Tanzania”

This book chronicles how Laeticia successfully challenged her removal from employment.

Laeticia was one of 15,000 workers made redundant in Tanzania in 1985 as a result of intervention from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. But in the large state-owned company for which she worked, she was the only woman among seven top-level managers and the only person actually dismissed.

Post Abolished is the telling and vivid narrative of her courageous campaign for reinstatement, the first case of its kind in Tanzania. It raises questions about equal opportunities policy relevant not only in developing countries but world-wide. Legislation, she found, is not enough, even in an exceptionally progressive legal system. She needed the support of her trade union and of courts. And that support had to be won. Institutions, she found, are staffed by individuals, most of them men, brought up in old patriarchal traditions. They make assumptions about women’s roles and men’s rights to authority, and react with unseen alliances between the public office and family structures.

This is a historically immensely important case study, essential reading to all involved with problems of economic and political development, of women’s rights, employment law and family law, trade union practice and labour relations.